Jcp Reward Code Serial Number October 2013

© Crown copyright 2015 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email:. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/summer-budget-2015/summer-budget-2015. Executive summary This is a Budget that puts security first. It ensures economic security for working people by putting the public finances in order and setting out a bold plan for a more productive, balanced economy. It supports national security by investment in defence.

It sets out bold reforms on tax and welfare, and introduces a National Living Wage so we move Britain from a low wage, high tax, high welfare economy to a higher wage, lower tax, lower welfare economy. It delivers on the promises on which the government was elected. Since 2010, the government has pursued a long-term economic plan that has halved the deficit as a share of GDP. For the first time since 2001-02, the national debt is falling in 2015‑16, meeting the target set out in 2010. The UK was the fastest growing G7 economy in 2014, employment has reached record levels, and wages are rising above inflation. But the job is not yet done. At 4.9%, the deficit remains too high, and productivity remains too low.

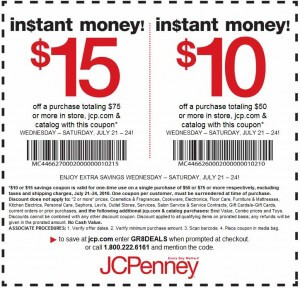

Mar 25, 2013. Click here for a new JCP $10 off $25 Printable Coupon/Online Code just in time for Mother's Day! Coupons are valid through March 25-31, 2013. To shop JCP online, you can take $10 off a $25 purchase when you use the coupon code in the email along with the non-transferable serial number included.

The economy is still too unbalanced, and more needs to be done to build up the nations and regions of the UK, and to close the productivity gap between the north and south. The welfare bill is too high, and the welfare system traps too many people in benefit dependency. And for too long, the government has addressed low pay by subsidising it through the tax credit system, instead of delivering lower business taxes and asking business to pay higher wages.

The UK economy and public finances 2.1 UK economy The government’s long‑term economic plan has secured the recovery. The government’s fiscal responsibility has allowed monetary activism to support demand in the economy alongside repair of the financial sector.

This has been supported by supply-side reform to deliver sustainable increases in standards of living. The UK’s economic recovery is well established. The UK was the fastest growing G7 economy in 2014 growing by 3.0%, its best performance since 2006. The Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development ( OECD) forecasts the UK to be the fastest growing G7 economy again in 2015, as shown in Chart 1.1. Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund ( IMF), said “when we look at the comparative growth rates delivered by various countries in Europe it’s obvious that what is happening in the U.K. Has actually worked”. Chart 1.1: GDP growth in the G7.

The government’s long-term economic plan has laid solid foundations for a stronger economy. This Budget continues the work of repairing the public finances, addressing the long-standing weakness in productivity and rebalancing the economy. It recognises the risks from abroad and the need to secure Britain’s economic future. 2.2 Employment and earnings Employment The UK labour market performance continues to be strong. In the 3 months to April the employment level and rate were both around record levels at 31.1 million and 73.4% respectively. The recent growth in employment predominantly reflects increases in full-time employment and those employed in high and medium-skilled occupations. Over the past year, 85% of the increase in employment has been in full-time work and 92% has been in high or medium-skilled jobs.

The proportion of those who are inactive has been falling and is lower than it was before the crisis, but there are still too many working-age people who are not engaged in the labour force. Encouragingly, the increase in participation has been strong amongst women and older workers.

The number of working-age women participating in the labour force has increased by over 700,000 since the beginning of the crisis. In the past year alone there have been an extra 200,000 workers aged over 50 in the labour force. The UK’s labour market has stood out among major advanced economies. Since the trough in the recession, the UK’s increase in employment rate has been the second largest in the G7 behind only Germany. The UK has taken another step towards achieving the government’s full-employment ambition to have the highest employment rate in the G7, having overtaken Canada in Q1 2015 to have the third highest employment rate in the G7, behind Japan and Germany, as shown in Chart 1.2. Chart 1.2: International comparison of employment rates. Earnings Earnings growth is continuing to strengthen with earnings up 2.7% over the year in the 3 months to April, the fastest growth in real wages since 2007.

The OBR forecasts earnings to continue to rise above inflation over the forecast period, as shown in Chart 1.3. The low inflation recently experienced in the UK, driven by lower fuel and food costs, has helped support real incomes and household budgets. Compared to May 2014, fuel and food prices are 11.0% and 1.8% lower respectively. Chart 1.3: Earnings growth and inflation. Real Household Disposable Income ( RHDI) per capita is the most up to date and comprehensive measure of living standards as it takes into account employment levels, the effects of tax and benefits, as well as inflation. Living standards, as measured by RHDI per capita, are forecast to be higher in 2015 than they were in 2010 and to continue to grow over the forecast period. 2.3 The UK’s productivity challenge A sustained improvement in productivity growth is critical to delivering the OBR’s forecast for the economy.

It is also the single most important determinant of average living standards and is tightly linked to the differences in wages across countries. A large and long-standing productivity gap exists between the UK and other major advanced economies. Output per hour in the UK was 17 percentage points below the G7 average, 27 percentage points below France, 28 percentage points below Germany and 31 percentage points below the US in 2013, as shown in Chart 1.4. This gap existed prior to the financial crisis but, whilst the UK has not been alone in having weak productivity growth since the financial crisis and there are issues around the data, it is clear this gap has widened. The recent weakness in productivity growth has also occurred alongside strong employment growth in the UK.

Chart 1.4: Productivity gap with the UK in 2013. The government is committed to reforming the UK economy to make it more productive.

The government is publishing a productivity plan which tackles the UK’s serious long-term challenges, with major reforms to improve the UK’s infrastructure, tackle failures in the skills system, improve the planning system, encourage long-term finance for productive investment and give cities the governance and powers they need to succeed. Further information on the government’s plan to support productivity is set out below, in ‘Backing business and improving productivity’. 2.4 Rebalancing the UK economy Regional rebalancing London is one of the world’s greatest global cities and a huge asset for the national economy, but in recent decades the UK has relied too heavily on the capital to generate growth.

The UK’s continued national prosperity depends on regions and cities outside the capital doing well. The government has a comprehensive plan to rebalance the economy and strengthen every part of the UK, bringing together the great cities and counties of the north of England, and supporting other vital regional economies such as the Midlands and South West. Since 2010 unemployment has fallen in every region and almost two-thirds of the UK-wide increase in private sector employment can be attributed to regions outside London and the South East. Output per head in the North West, North East, West Midlands and Wales grew faster than in London in 2013.

The government will go further by supporting the resurgence of strong metro-wide areas through devolution, enabling cities to work together to take responsibility for their own economic success by the creation of an elected mayor. Further information on the government’s plan is set out below, in ‘Ensuring a truly national recovery’.

Sector rebalancing As the recovery has become established, growth has been more broadly balanced across sectors. There has been widespread growth across all major sectors since the start of 2013. Manufacturing, construction and services all grew by 3% or more in 2014, the first time since records began in 1990. After falling during the crisis, recent UK growth has been more investment rich with business investment increasing as share of GDP.

Real business investment has increased from 9.0% of GDP in 2010 to 10.6% of GDP in 2014 and is forecast to continue to do so. However, total investment as a share of output in 2014 was still lower in the UK than all other major advanced economies except Italy. This is addressed in the productivity plan which will set out measures to encourage long-term investment in economic capital, including infrastructure, skills and knowledge.

External rebalancing The UK is one of the most open economies in the world, with significant trade and financial links with other countries. Weak euro area growth has meant goods exports to EU countries have been subdued, falling by 5.3% since Q1 2008.

However UK exports have continued to expand in other markets, as shown in Chart 1.5. The volume of goods exports to outside of the EU has increased by 24.1% since Q1 2008.

The value of goods exports to the faster growing BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) economies has increased by 25.1% since Q1 2008. Chart 1.5: Trade in goods since 2008. The UK’s trade balance as a share of GDP has improved slightly from -2.4% in 2010, to -2.0% in 2014 and is expected to improve further in 2015. The OBR’s forecast for exports and imports over the forecast period reflects the slowdown in global trade volumes that has been seen since the early 2000s. For any level of world GDP, world trade is now expected to be lower and this feeds into a weaker outlook for UK trade, with other advanced economies also expecting to see lower exports in the next few years. The current account deficit was 5.9% of GDP in 2014. The income balance component of the current account has declined since early 2012, reflecting lower income received from investment abroad.

Weaker euro area growth and global prospects have seen UK investments abroad yield lower returns while, in contrast, as the UK economy has continued to recover, the payments made on foreign investments in the UK have increased. The authorities remain vigilant to any risks that may emerge. The UK’s large current account deficit contributes to the UK running the largest combined government and current account deficits in the G7, as shown in Chart 1.6. A current account deficit means the UK is a net foreign borrower and is acquiring more foreign liabilities than assets. The UK has run a persistent current account deficit for 30 years and a small deficit is sustainable with continued capital inflows. The UK’s budget deficit and debt position is in part financed by these capital inflows through purchases of UK government gilts. In comparison, countries that have higher levels of public debt but run small current account surpluses, such as Italy and Japan, are less exposed to financing risks from a shift in overseas invester sentiment.

The government’s fiscal plan to complete the repair of the public finances should support a gradual narrowing of the current account deficit and reduce this exposure. Chart 1.6: Combined government and current account deficits in the G7 in 2014. Housing market and households House price growth has moderated over the past year, having grown strongly during early 2014, with annual house price growth slowing to 5.5% in April 2015. Meanwhile, property transactions fell during the second half of 2014 and were 3.1% lower in May 2015 than a year earlier. The OBR forecasts house prices to grow by 5.7% in 2015, followed by 4.1% in 2016, before rising to 5.6% in 2020.

Property transactions are forecast to fall by 1.7% in 2015 before growth picks-up, peaking at 5.5% in 2018. Household balance sheets have continued to normalise as households have reduced their debt as a proportion of income to 145% in Q1 2015, having peaked at 169% in Q1 2008. While households take on debt over the forecast period they also accumulate assets, meaning household net wealth as a proportion of income is forecast by the OBR to increase from 8.3 times income in 2014 to 8.6 times income in 2020.

2.5 Global developments The strength and sustainability of the global economic recovery is key to UK economic prospects. The global economic recovery remains uneven and the risks from the world economy, not least from within the euro area, demonstrate the need to continue to fix the economy to ensure the UK can deal with risks from abroad. In June 2015 the OECD revised down its global growth forecast for 2015 from 3.7% (forecast in November 2014) to 3.1%, with the global recovery gaining momentum but slowly. The OECD revised down its forecast for US growth in 2015 from 3.1%, forecast in its March interim forecast, to 2.0%, while the euro area growth forecast was left unchanged at 1.4% in 2015.

China’s growth is expected to moderate and to fall below 7% in 2015 to 6.8%. The IMF last updated its economic forecast in April 2015 and forecast global growth at 3.5% in 2015.

The IMF’s forecast included a marked shift in prospects across countries, with upward revisions in the euro area, Japan and India, and downward revisions for some emerging markets and the US. The IMF will publish its revised global growth forecast on 9 July and the forecast will reflect developments over Q1 2015. Euro area growth in Q1 2015 was 0.4%, though the recovery remains vulnerable. The US 2015 growth forecast was revised down in the IMF’s June Article IV review to 2.5%, in light of weak Q1 2015 data. A number of other downside risks to the global recovery remain, including: • the clear risk that the ongoing situation in Greece spills over, causing renewed instability • the risk of renewed weakness in growth and inflation in the euro area • the risks posed to emerging markets with weak fundamentals from US rate rises and dollar appreciation • an escalation of geopolitical risks • the challenge for China in undertaking reform while maintaining financial stability The financial crisis in Greece is the biggest single external risk to the UK economy. It is vital that the current uncertainty is resolved, to ensure economic and financial stability across Europe.

Britain will be more affected the longer the Greek crisis lasts, and the worse it gets. The government will do whatever is necessary to protect the UK’s economic security at this uncertain time.

To deliver prosperity and security for all, the EU needs to be dynamic and outward focused, putting its resources to the most effective use. It must empower businesses to compete more effectively internationally by accelerating the integration of the single market, especially in services, and the financial, digital and energy sectors. Epson Aculaser M2000 Driver Windows 7 32bit.

Part of this would be the strengthening of the regulatory framework for business, improving the quality of regulation, and reducing excessive regulatory burdens on business. The EU also needs to be open to international trade and complete free-trade agreements with the US, Japan, and other developed economies, whilst also looking towards important new trading partners in Asia and South America. The government has a clear plan of reform, renegotiation and referendum, to make the EU a source of growth, jobs, innovation and success. The EU must make sure the interests of both those inside and outside the euro area are fairly balanced.

The single currency is not for all member states in the EU, but the single market and the EU as a whole must work for all. The UK has joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank ( AIIB) as a founding member, following the announcement in March that the UK would be the first G7 member to apply to join. The UK’s involvement from the outset will help ensure that the AIIB embodies the best standards in accountability, transparency and governance, and help maximise the opportunities for British businesses and British jobs. Any strategy for long-term debt reduction must also take into account the UK’s low inflation environment. Independent monetary policy now delivers low and stable medium-term inflation, to the benefit of the whole economy. This contrasts with the experience after World War II, when very high inflation, together with financial repression, played a major role in reducing debt. Substantial debt reduction in future will depend on responsible management of the public finances and sustainable economic growth.

The only reliable way to bring debt down to safer levels is to run a surplus in normal times. Running a surplus will mean that debt falls rapidly when the economy is growing normally – ensuring that long-term debt reduction will not be knocked off-course by periodic shocks. 2.10 Charter for Budget Responsibility The government has published a draft (the “Charter”) to entrench this commitment to reach an overall surplus and maintain it in normal times. The draft Charter sets out: • a target for a surplus on public sector net borrowing in 2019-20, and a supplementary target for public sector net debt to fall as a share of GDP in each year from 2015-16 to 2019-20 • a target, once a surplus is achieved in 2019-20, to run a surplus each subsequent year as long as the economy remains in normal times These targets will apply as long as the economy is not hit by a significant negative shock that reduces real GDP growth to less than 1% (on a rolling 4 quarter-on-4 quarter basis). If the OBR judge that the economy has been hit by a shock, the surplus rule will be suspended. This will allow the automatic stabilisers to support the economy when they are needed. The framework therefore supports fiscal discipline in normal times, while ensuring that future governments will have the flexibility to respond appropriately to shocks.

Following a shock, the government of the day will be required to set a plan to return to surplus. This plan must include appropriate fiscal targets. The framework does not prescribe what the targets should be, allowing the government of the day to respond to the circumstances. However, the targets will be voted on by the House of Commons and assessed by the OBR. A surplus in normal times is necessary to provide the government of the day with the fiscal space to allow appropriate action to be taken in the face of these shocks. The end goal must be to return the public finances to surplus, ensuring that long-term debt reduction continues. The Charter will be laid before Parliament and voted on by the House of Commons in the autumn of 2015.

2.11 The OBR’s fiscal forecast As a result of the government’s plan, the OBR is forecasting that the public finances will return to surplus in 2019-20. The surplus in 2020-21 would be the largest structural surplus in 40 years. Table 1.4 sets out the OBR forecast for key fiscal aggregates over this Parliament, based on the strategy defined in this Budget. From its post-war peak of 10.2% of GDP in 2009-10, PSNB is forecast to fall to: • 3.7% of GDP in 2015-16 • a surplus of 0.4% of GDP in 2019-20 and 0.5% of GDP in 2020-21 PSND is forecast to peak at 80.8% of GDP in 2014-15, before falling each year and reaching 68.5% of GDP in 2020-21. 2.12 Fixing the public finances and returning a surplus The government has set out its fiscal plan, to consolidate at the same pace on average as the last Parliament to reach a surplus in 2019-20.

This is a smoother path of consolidation than was planned in March, but will still require action in order to achieve the surplus. The sections below set out the measures the government will undertake over this Parliament to repair the public finances. These measures also deliver by 2019-20 the planned contributions of £5 billion from avoidance and tax planning, evasion and compliance, and imbalances in the tax system, and £12 billion from welfare. Plans to deliver the remaining consolidation will be set out in the autumn following a rigorous Spending Review process. Tax The government believes in lower taxes, and is committed to eliminating the deficit in a way that is fair to taxpayers. The cornerstone of this commitment is to introduce into legislation a tax lock to rule out increases in the main rates of income tax, VAT or National Insurance over the course of this Parliament.

This Budget addresses imbalances in the tax system in order to pay for tax reforms to support individuals and businesses. By 2017-18, 8 out of 10 working households will be better off as a result of the income tax Personal Allowance, living wage and welfare (including tax credits) changes in this Budget. On average, these households will be £130 per year better off.

The majority of individuals and businesses pay their fair share of tax. However, there are some who fail to pay what they owe due to error or a failure to comply with their obligations as a taxpayer, and a small minority who try to evade or aggressively avoid paying the tax they should. As part of its consolidation plans, the government will raise at least an additional £5 billion a year by 2019-20 by tackling avoidance and tax planning, evasion and compliance, and by addressing imbalances in the tax system. Further details of measures to ensure that individuals and businesses pay what they owe, and to address imbalances in the tax system, are set out later in this chapter. 2.13 Welfare The government’s welfare cap is a firm limit on welfare spending, applying to spending in Annually Managed Expenditure with the exception of the state pension and the automatic stabilisers. Consistent with the Charter for Budget Responsibility, the government is setting the welfare cap for this Parliament in this Budget. The welfare cap is set at the level of the OBR’s forecast for spending in scope of the cap.

The cap therefore reflects the welfare savings announced at this Budget, and improvements in the forecast since the cap was last set at Budget 2014. By setting the cap at the level of the new forecast, the government is committing to deliver the welfare savings set out at this Budget. The forecast margin will be set at 2% of the new cap. Table 1.7: Welfare cap £billion 20-18 20-20 2020-21 Welfare cap 115.2 114.6 114 113.5 114.9 Forecast margin (2%) 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 Source: HM Treasury, based on Office for Budget Responsibility forecast. In the last Parliament, the government legislated for over £21 billion of welfare savings. As the recovery takes hold, it is right that welfare savings continue to play a role in the deficit reduction plan.

The government’s plans for reducing the working-age welfare bill are set out below. The government is reforming the welfare system to make it more affordable and fairer to taxpayers, while continuing to support the most vulnerable.

As a result of measures announced in this Budget, welfare spending will be £12 billion lower in 2019-20 than would otherwise have been the case. Working-age welfare spending is now forecast to grow at -2.3% annually in real terms over the Parliament, compared to -0.6% over the last Parliament and 4.0% over the 2005-10 Parliament. Public spending The government has already identified a further. The departmental savings have been achieved through efficiency savings, tighter control of budgets to drive underspends in-year, and through asset sales. The government will set out how the remaining consolidation will be delivered in the autumn following a rigorous Spending Review process. The Spending Review will look at all elements of public spending in order to create a more efficient public sector, whilst continuing to prioritise growth-promoting expenditure and spending on public services for those who need them the most. Funding for healthcare The NHS ‘Five Year Forward View’ outlines a plan for a more sustainable, integrated health service that cares for people closer to home. The Budget protects spending on the NHS in England and backs its 5-year plan.

The government will continue to spend more on the NHS in real terms every year, as it has in every year since 2010. It will fully fund the NHS plan which called for £8 billion more by 2020-21. This additional funding comes on top of the £2 billion announced at Autumn Statement 2014.

The Budget therefore commits to increase NHS funding in England by £10 billion in real terms by 2020-21, above 2014-15 levels. This additional investment will support the NHS in England to go further than its plan and to deliver a step change in safety, quality and access. The Five Year Forward View set out how, with the additional funding confirmed in this Budget, the NHS will deliver £22 billion in efficiency savings by 2020-21. This will come through improvements to quality of care and staff productivity, and better procurement. The government will ensure the NHS becomes a 7-day service by 2020-21. Hospitals will be appropriately staffed at weekends to ensure people can obtain the care they need every day of the week.

Everyone will be able to access GP services from 8am – 8pm seven days a week. These improvements will allow people to better balance work, health and family and will be a key to a more productive economy. Funding for defence and security The first duty of government is to ensure the safety and security of the country and its people. The government remains committed to ensuring real growth of the Ministry of Defence equipment plan of 1% per year and maintaining the size of the Army at 82,000. The government will go further, and this Budget commits to raise the entire Ministry of Defence budget by 0.5% a year in real terms. This Budget also protects overall counter terrorism spending across government, a total of more than £2.0 billion spent by a range of departments, agencies, and the police. The threats the UK faces are diverse and require coordinated responses from the armed forces, security and counter terrorism agencies.

In addition to the annual increase in the defence budget, this Budget announces up to an additional £1.5 billion a year by the end of the Parliament to fund increased spending on the military and intelligence agencies by an average of 1% a year in real terms. The final allocation of this additional funding will be determined by the Strategic Defence and Security Review and Spending Review, and is conditional on the armed services and agencies producing further efficiencies within their existing budgets to ensure continued investment in the most important capabilities. Allowing for all of the public spending that supports the Ministry of Defence and the contribution made by the secret intelligence agencies, this Budget commits the government to meet the properly measured NATO pledge to spend 2% of national income on defence every year of this decade. Public sector pay and pensions In the last Parliament, the government exercised firm restraint over public sector pay to deliver reductions to departmental spending, saving approximately £8 billion.

As set out by the Chancellor at Autumn Statement 2014, the government will need to continue to take tough decisions on public sector pay in order to deliver reductions to departmental spending and protect the quality of public services. Overall, levels of pay in the public sector are now, on average, comparable to those in the private sector. However, public sector workers continue to benefit from a significant premium once employer pension contributions are taken into account, as shown in Chart 1.10. Chart 1.10: Estimated public-private hourly pay differential.

In light of this and continued low inflation, the government will therefore fund public sector workforces for a pay award of 1% for 4 years from 2016-17 onwards. This will save approximately £5 billion by 2019-20. The government expects pay awards to be applied in a targeted manner within workforces to support the delivery of public services. As part of the forthcoming Spending Review, the government will continue to examine pay reforms and modernise the terms and conditions of public sector workers. This will include a renewed focus on reforming progression pay, and considering legislation where necessary to achieve the government’s objectives. The government will work with Local Government Pension Scheme administering authorities to ensure that they pool investments to significantly reduce costs, while maintaining overall investment performance. Efficiency and reform The government will continue to pursue more efficient ways of working and further reform to public services.

The government will provide funding for the Cabinet Office to explore a number of cross-cutting savings proposals. The Treasury, working with Cabinet Office, will develop specific proposals to inform the Spending Review. At Spending Round 2013, the government announced a control total would limit payments under PFI and PF2 contracts in nominal terms in each future Parliament. As reported by the OBR, the Treasury is on track to meet this target, with forecast cumulative spending from 2015-16 to 2019-20 for payments on all PFI contracts funded by central government standing at £51.9 billion. BBC The BBC has agreed to take on responsibility for funding the over-75s licence fee concession, which will help contribute to reductions in public spending.

This will be phased in from 2018-19, with the full liability being met by the BBC from 2020-21. As part of these new arrangements, the government will ensure that the BBC can modernise the licence fee to cover public service broadcast catch-up television and anticipates that the licence fee will rise in line with CPI over the next Charter period, subject to Charter Review conclusions on the purposes and scope of the BBC, and the BBC demonstrating that it is undertaking efficiency savings at least equivalent to those in other parts of the public sector. Financial sector and other state-owned asset sales The government is committed to returning the financial sector assets that were acquired in 2008 and 2009 to the private sector.

The government will seek to dispose of other commercial and financial assets, which there is no policy reason for the government to hold, in order to maximise value for taxpayers and reduce the level of public debt. Significant progress towards this goal has already been made. 2.14 Performance against the fiscal mandate The government’s fiscal strategy, as set out in the current published during the last Parliament, is underpinned by the forward-looking mandate to balance the cyclically-adjusted current budget by the end of the third year of the rolling 5-year forecast period. The government remains on course to meet the current fiscal mandate, with the OBR forecast indicating that cyclically-adjusted current budget balance will be achieved a year early in 2017-18.

The government’s fiscal mandate is supplemented by a target for PSND as a percentage of GDP to be falling in 2016-17. The OBR forecasts PSND falls 1.1% of GDP between 2015-16 and 2016-17. Additionally, PSND as a share of GDP will start to fall one year earlier in 2015-16. This will be the first time that PSND has fallen as a share of GDP since 2001-02. The OBR forecasts that the government is on course to meet the new fiscal mandate proposed in the Budget to reach an overall surplus in 2019-20, and the new supplementary target for debt as a share of GDP to be falling in every year to 2019-20. 2.15 Performance against EU deficit targets The government remains committed to bringing the UK’s Treaty deficit in line with the 3% target set out in the Stability and Growth Pact ( SGP). The current forecast indicates that this target will be met in 2016-17.

2.16 Debt and reserves management The government’s revised financing plans for 2015-16 are summarised in Annex A. The debt management framework was set out in the ‘’, published alongside the March Budget 2015, and this framework remains in place. National Savings and Investments ( NS&I) have a net financing target which remains at £10.0 billion in 2015-16, within a range of £8.0 to £12.0 billion.

The net financing requirement for the Debt Management Office ( DMO) is projected to fall by £14.0 billion to be £123.9 billion. It is planned that this will be met through gilt issuance of £127.4 billion and a reduction of £3.5 billion in the stock of Treasury bills. The financing arithmetic provides for £5.3 billion of sterling financing for the Official Reserves in 2015-16, as set out in the Revision to the DMO’s Financing Remit 2015-16 on 23 April 2015. The government is planning on the basis of sterling financing for the Official Reserves of £6 billion per year on average, over the 4 years from 2016-17 up to and including 2019-20; thereafter the government has adopted a neutral assumption.

Rewarding work and backing aspiration Underpinning the government’s approach is a commitment to reward work and back aspiration, while continuing to support the most vulnerable in society. Belajar Bahasa Korea Untuk Pemula Pdf Editor there. This Budget builds an economy where people get a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work by earning more and keeping more of what they earn. It ensures that welfare expenditure is controlled and that the welfare system is fair to taxpayers who pay for it. The Budget will support working people by introducing a new National Living Wage (NLW) to lift the wages of the lowest paid, while setting out the path to a tax-free National Minimum Wage ( NMW). The Budget cuts taxes so working families can keep more of what they earn by raising the personal allowance and delivering a real terms increase in the higher rate threshold of income tax for the first time since 2010.

And it will take the family home out of inheritance tax for all but the wealthiest. The Budget reforms welfare so that it is fair both to those who need it, and those who pay for it. It makes the whole system more sustainable and rewards work. The Budget ensures the deficit is cut in a fair way by taking significant action to tackle tax avoidance and aggressive tax planning, tax evasion and compliance, and address imbalances in the tax system. The UK’s strong labour market has resulted in a substantial fall in income inequality, with inequality in original incomes (before taxes and benefits) now at its lowest point for 25 years. In addition, as a result of the decisions of this government and the previous government, the poorest fifth of households receive the same proportion of public spending (24%) as they did before consolidation. However, tax decisions have shifted the burden onto the rich: before consolidation, the richest fifth paid 49% of tax; this has increased to 52%.

3.1 A higher wage, lower tax, lower welfare society The government wants to move from a low wage, high tax, high welfare society to a higher wage, lower tax, lower welfare society. Over the last Parliament, those on the lowest wages saw their pay steadily rise, with the NMW now standing at £6.50.

Tax reforms took millions of people out of income tax and reduced income tax for millions more. Flagship welfare reforms have started to bring expenditure under control and ensure that the system rewards work. And the government is delivering on its pledge to create full employment. In the last Parliament, the Jobseeker’s Allowance claimant count reached its lowest ever level, 2 million new jobs were created and the UK recently overtook Canada to have the third highest employment rate in the G7. With a record high of 31.1 million people now in employment, record levels of vacancies, and an economy that was the fastest growing in the G7 in 2014 and is forecast by the OECD to be the fastest growing again in 2015, the government will take further steps towards the vision of an economy and society where people are better paid and keep more of what they earn, instead of relying on an ever increasing benefit system. 3.2 A higher wage society: the National Living Wage The UK has a higher incidence of low pay than other advanced economies: 1 in 5 UK workers is low-paid, compared to an average of only 1 in 6 among OECD countries.

With a strengthening economy, the government believes that now is the right time to take action to tackle low pay and ensure that lower wage workers can take a greater share of the gains from growth. The government will therefore introduce a new National Living Wage (NLW) for workers aged 25 and above, by introducing a new premium on top of the NMW. From April 2016, the new NLW will be set at £7.20 – a rise of 70p relative to the current NMW rate, and 50p above the NMW increase coming into effect in October 2015. The government will ask the Low Pay Commission (LPC) to set out how the new NLW will reach 60% of median earnings by 2020. Based on the OBR’s earnings forecasts, this means that the NLW will reach the government’s target of over £9 by 2020. 60% of median earnings is in line with the approach suggested by Professor Sir George Bain, the first chair of the LPC, in a 2014 report on the future on the NMW. This will mean a direct boost in earnings for 2.7 million low wage workers, and the OBR have indicated that knock-on effects further up the wage distribution could mean a further 3.25 million people also see an increase in wages as a result of the NLW.

By the end of the Parliament, an individual aged over 25 working 35 hours a week and previously earning the NMW will see their gross wages increase by around a third compared to 2015-16, or £5,200 in cash terms. This is equivalent to an extra £2,000 per year from the premium alone, £4,000 for a couple. The chart below sets out the expected profile of the NLW, based on OBR forecasts. Chart 1.12: National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage, historical and forecast. Alongside the Budget, the government has published an entirely. To ensure that the rate of the NLW is set at a sustainable level and continues to take account of broader economic conditions, the LPC’s remit will require it to set the NLW in a way that reflects the growth in median earnings. The LPC’s remit in relation to the NMW will remain unchanged.

For younger workers, the priority is to secure work and gain experience, which is already reflected in the existing NMW rate structure. In order to maximise the opportunities for younger workers to gain that experience, the NLW will only apply to workers aged 25 and over. The wages of younger workers will continue to be underpinned by the core NMW. The government recognises that this new NLW may increase costs for some businesses.

Therefore on top of other reductions in business tax, from April 2016, the government will increase the National Insurance contributions ( NICs) Employment Allowance from £2,000 to £3,000 a year. This will help all businesses and charities, particularly smaller ones, with additional wage costs.

As a result, up to 90,000 employers will see their employer NICs liability reduced to zero. When introduced in 2014, the Employment Allowance offset the NICs costs of employing 4 workers full time on the NMW. The increase in the Employment Allowance will mean firms will be able to continue to employ 4 workers full time on the new NLW next year, without paying any NICs. The further reduction in the rate of corporation tax will also cut costs for businesses, as will reforms to the Annual Investment Allowance (set out in more detail in ‘Backing business and improving productivity’). The OBR estimate that the increased cost to businesses from the NLW could amount to only just over 1% of corporate profits by 2020. The economic impact of a National Living Wage The concept of setting a minimum wage target based on 60% of median earnings was set out in a recent report by the Resolution Foundation, authored by the first chair of the LPC Professor Sir George Bain, along with others including Professor Alan Manning, as part of a more ambitious approach to low pay with additional focus on the longer term impacts.

The introduction of a NLW will reduce the incidence of low pay and increase the returns to entering work. There may also be an increase in costs for businesses, which could affect employment. The OBR assessment of the impact of the introduction of a National Living Wage, given the continued strong employment growth seen in the UK, is to have “revised up fractionally” their forecast for unemployment rate. They estimate that even after the introduction of the new NLW, employment is forecast to rise by 1.1 million in 2021 – only 60,000 lower than it would have risen without the NLW. While some empirical studies have found reductions in employment from increases in the minimum wage, these have generally been modest. Other studies have been unable to find robust evidence of any negative employment effect. Indeed, in 2001, the adult minimum wage increased by 10.8% in a single year.

Further strong rises in 2003 and 2004 resulted in the minimum wage increasing by 31.1% over four years. Here, the evidence suggests that there was not a large impact on employment. Summarising the existing research, the LPC stated in 2011 that, “The consensus of the research findings on the impact of the NMW in the UK is that it has not significantly adversely affected employment but that it may have had a small negative impact on hours.” Instead firms have adjusted through other channels, by adjusting profits and pricing strategies, changing pay differentials and, in low paying sectors, boosting productivity.

Employers’ costs are also being lowered by other measures in the Budget, including reductions in the rate of Corporation Tax, and an increase in the Employment Allowance. 3.3 A lower tax society: cutting taxes for working people Alongside action on wages, the government is supporting working people by ensuring that they can keep more of the money they earn by cutting taxes. Income tax In the last Parliament, the personal allowance increased by more than 60%, from £6,475 in 2010-11 to £10,600 in 2015-16. It is delivering a tax cut for over 27 million individuals, with basic rate taxpayers being £825 better off in 2015-16 compared with 2010. As a result, 3.8 million individuals on the lowest incomes were removed from income tax altogether, addressing the merry-go-round of taking taxes off people only to repay them in benefits. The government wants to continue to reward work by reducing taxes and taking more people out of income tax. The government has therefore pledged to raise the personal allowance to £12,500 by the end of this parliament.

This Budget takes the first step towards this commitment. In 2016-17, the personal allowance will increase by £400 to £11,000. As a result, a basic rate taxpayer will be £80 better off in 2016-17 compared to 2015‑16, and £905 better off compared with 2010. The government believes that people working 30 hours a week on the lowest pay (the NMW) should not pay income tax. The government will therefore legislate to ensure that once the personal allowance has reached £12,500, it will always be set at least at the equivalent of 30 hours a week on the NMW. This will ensure that those working up to 30 hours on the NMW will not pay income tax in the future.

Chart 1.13: Annual gross salary for 30 hours per week at National Minimum Wage and Personal Allowance. The government wants to encourage those who aspire to progress in work. That is why the government has pledged to raise the level at which the higher rate of income tax is applied, the higher rate income threshold, to £50,000 by the end of this parliament. This Budget confirms the first step towards this commitment by increasing the higher rate threshold from £42,385 to £43,000 for 2016-17. This is the first time since 2010 that the higher rate threshold will go up by more than inflation alone.

These changes will lift 130,000 individuals out of higher rate tax by 2016-17, compared to 2015-16. A typical higher rate taxpayer will benefit by £142 in 2016-17, and will be £818 better off compared to 2010. 3.4 A lower welfare society: reforming the system to make it fairer and more affordable In the last Parliament, the government started reforming the welfare system to make it fairer and more affordable, legislating for £21 billion of savings. Universal Credit, which brings together 6 benefits into 1, represents the most fundamental reform of welfare since its inception and will mark a turning point towards a system where work will always pay more than a life on benefits. Universal Credit is due to expand to over 500 jobcentres by the end of this year.

However, despite progress during the last Parliament there is still more to do. Taxpayers are still being asked to pay for welfare expenditure that remains disproportionately high. 7% of global expenditure on social protection is spent in the UK, despite the fact that the UK produces 4% of global GDP and has only 1% of the world’s population.

As chart 1.14 shows, spending on working-age welfare has increased significantly in real terms over the last few decades. Too many families continue to be trapped on benefits. The Budget sets out the next stage of welfare reform, delivering on the government’s commitment to save £12 billion from the working age welfare bill.

Chart 1.14: Working age welfare (2014-2015 prices). Freezing working-age benefits Since the financial crisis began in 2008, average earnings have risen by 11%, whereas most benefits, such as Jobseeker’s Allowance, have risen by 21%. To ensure that it always pays to work, and that earnings growth overtakes the growth in benefits, the government will legislate to freeze working-age benefits, including tax credits and the Local Housing Allowances, for 4 years from 2016-17 to 2019-20. This is forecast to save £4 billion a year by 2019-20. Statutory payments, including Maternity Allowance, Maternity Pay, Paternity Pay and Statutory Sick Pay will continue to be indexed by CPI. Disability benefits will also continue to be indexed by CPI, including Personal Independence Payment, Attendance Allowance, Disability Living Allowance and Employment and Support Allowance (Support Group). The government will continue to protect benefits which are specifically for pensioners.

The ‘triple lock’ on the State Pension will be maintained; and other benefits for pensioners including the Winter Fuel Allowance and free TV licences for over 75s will be protected in this Parliament. Pensioners have paid into the system throughout their working lives, and are the group least able to increase their income in response to welfare reform. Alongside the freeze in working-age benefits, the government will reduce rents in social housing in England by 1% a year for 4 years, requiring Housing Associations and Local Authorities to deliver efficiency savings, making better use of the £13 billion annual subsidy they receive from the taxpayer. Rents in the social sector increased by 20% over the 3 years from 2010-11.

This will allow social landlords to play their part in reducing the welfare bill. This will mean a 12% reduction in average rents by 2020-21 compared to current forecasts.

Making Tax Credits and Universal Credit fairer Tax credit expenditure more than trebled in real terms between 1999-00 and 2010-11, with total expenditure in 2014-15 estimated to be around £30 billion – an increase of almost £10 billion in real terms over the last 10 years. UK expenditure on family cash benefits is the highest in the OECD, and was double the OECD average in 2011. 9 out of 10 families with children were eligible for tax credits in 2010. As a result of the reforms undertaken in the last Parliament, 6 out of 10 are eligible currently.

The government believes that.